My home is on the island of Tasmania, south of the Australian ‘mainland’. It is an incredible, unique, and special place. And in every way, Tasmanians are deeply connected to this place - its weather, beauty and resources are our identity, our economy, and our wellbeing. Nature is not a backdrop to our place in the world, it is central to our lives, our prosperity, and our responsibility.

On a recent Impact Safari through Scandinavia, I joined a group of Australian leaders and changemakers to explore how cities are grappling with the intertwined challenges of sustainability, democracy, and collective wellbeing - the familiar balance of nature, economy and liveability. Cycling through Copenhagen’s streets, swimming in Stockholm’s waterways, and walking in Oslo’s green spaces, I caught glimpses of what Scandinavia does differently, but also the echo of Tasmania’s own journey.

We met with dozens and dozens of incredible people - all telling their version of a story on place. Stories are powerful because they help us see systems. They remind us that landscapes, communities, and economies are not separate, but deeply connected. I felt that Scandinavia certainly offers lessons in embedding stewardship into everyday life, strategy, policy and governance, but Tasmania has something equally unique: extraordinary natural heritage alongside an established NRM model, and the deep wisdom of Country.

I have decided not to simply tell the story of what I saw and heard; it’s not a story of “them and us”. I wanted to tell stories of exchange. So, I’ve developed a series of interconnected stories. They are lenses through which I try to reflect on what we might learn, what we might adapt, and what we already hold that the world could learn from. These are stories that are inspiring me invite us to imagine a Tasmanian future where people and nature thrive together.

Story 1: Listening for the voice of nature

Swimming as a measure of care

Did you know there is a simple test for how a place values its own life: do people swim in its water without worry?

In Copenhagen, locals slip into the harbour before breakfast. It’s a quiet, ordinary, daily habit. And it is the most tangible proof that a city once damaged by industrial use has deliberately chosen to restore its waterways and reconnect people to place.

The harbour’s return to health didn’t happen by accident. It was the product of decades of policy, design, community activism and civic pride. It was a sustained commitment to listen to the living systems that carry the city’s life.

“Restoration proves that loss is not always permanent. Nature, given the right conditions and the will to act, can recover.”

On our Impact Safari with the Small Giants Academy, those early morning strokes became a benchmark. They pointed to a wider story repeated in Stockholm and Oslo: care and restoration is contagious.

- In the Swedish lakes, I swam after seeing incredible moose, deer, foxes, red squirrel, birds and beavers.

- In Copenhagen, we swam as new friends alongside the locals like Marshall Blecher - right in the centre of the city.

- In Stockholm’s archipelago we swam after a life-changing sauna ceremony, walked islands where new marine protection had just been proclaimed, and saw galleries where artists translated biodiversity into images and sculptures that lingered.

- In Oslo, collaboration through groups like So Central and the idea of a swimmable river and fjord became a symbol of urban renewal, echoing Melbourne’s work on the Birrarung (Yarra River) and integrated catchment management (Australian NRM style).

These are not only environmental victories, they are cultural ones. They have shifted expectations of civic leaders and made nature visible again in everyday life.

Accessibility accelerates care.

When a child grows up leaping into clean rivers, or when a neighbourhood gathers beside an estuary, stewardship becomes instinct. Public swimming platforms, green corridors, and urban wetlands shift the baseline beyond GDP to wellbeing, identity and giving back (care). When people belong to place, they protect it.

Ecological and social benefits then follow. In NRM South’s own work, we’ve seen restoration lead to carbon storage in saltmarshes, flood buffering, healthier fisheries, and improved mental health.

The voice of nature

One of the stand out experiences for me was to hear Pella Thiel’s words on nature. The “voice of the herring” invited us to stretch our imaginations. What if rivers, wetlands, forests and seas were given a seat at the table during decision-making?

This was not a legal trick. It was an ethical shift, one that asked us to move from extraction to relationship, from command to conversation, from “resources” to kinship.

A series of workshops in the Stockholm archipelago and Joanna Macy-inspired ecopsychology exercises reminded us to “listen with our whole bodies.” To slow down, grieve, imagine, and hope. This matters because systems change begins inside us as much as in laws or models.

“Stewardship is cultural, relational, and intergenerational.”

I am bringing this home with me - in our work, we often communicate that we are ‘managing nature’. But it’s not enough - we need to really listen. Above all the noise, I’m trying to hear it.

What does Tasmania ask of us?

Scandinavia offers powerful models, but Tasmania already carries the ingredients for this story. We have community pride, glorious rivers, rich biodiversity, deep cultural connection to Country, and… an NRM network that knows how to bring people together for action!

The challenge is to elevate the voice of nature in decisions.

Some questions I’ve been pondering:

- Are we giving nature a seat at the table for future planning? What assumptions have we made about the value of nature?

- Have we recognised the past, current, and future role of Palawa custodianship?

- Can we move beyond conflicting views by activating citizen-led and participatory processes to codesign solutions?

- Do we openly recognise that restoration provides public as well as ecological benefit? Are we telling stories that translate science/action into community pride?

Pella Thiel invited us to imagine what our descendants might say if they could reach us through a time portal. I hope they would tell me that the ripples we began today created a future Tasmania where nature and restoration is accessible and celebrated, Aboriginal leadership is central, rivers and forests are treated as kin, and stewardship becomes a shared identity.

I invite you to reflect in the same way. Sit by the banks of a river and listen. The voice you hear will not only be nature’s voice, it will also be political, cultural and moral. It will ask for patience, courage and hope. And it will remind you that small, daily acts matter: planting, growing, sharing food, telling stories. Each is a ripple, and together they form the current that shapes Tasmania’s future.

“If we listen and act with policy, with story, and with science, we can reach through time and speak in a way our grandchildren will recognise and thank us for.”

Story 2: Designing the Future

Changing the system

Across Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Oslo, a pattern emerged. These are places deliberately changing the future by aligning design, democracy, and finance around long horizons.

Liza Chong of Dark Matter Labs showed us Copenhagen’s cycle bridges, Nordhavn’s mixed-use districts, and Copenhill to demonstrate how design shapes access, behaviour, and civic connection. And interestingly, how private business investment is contributing to this (corporate philanthropy is big in Denmark). As a part of Slussen’s redevelopment in Stockholm, Marta Bohlmark from Gaia Arkitektur, and Paula MacKenzie of White Architects, showed us that ecological design is social design. Restoring wetlands or planning blue and green corridors isn’t just about infrastructure, it’s about inviting participation, creating corridors for both people and species, and making stewardship visible.

“Design is political. When infrastructure invites people into nature, it creates civic belonging and stewardship.”

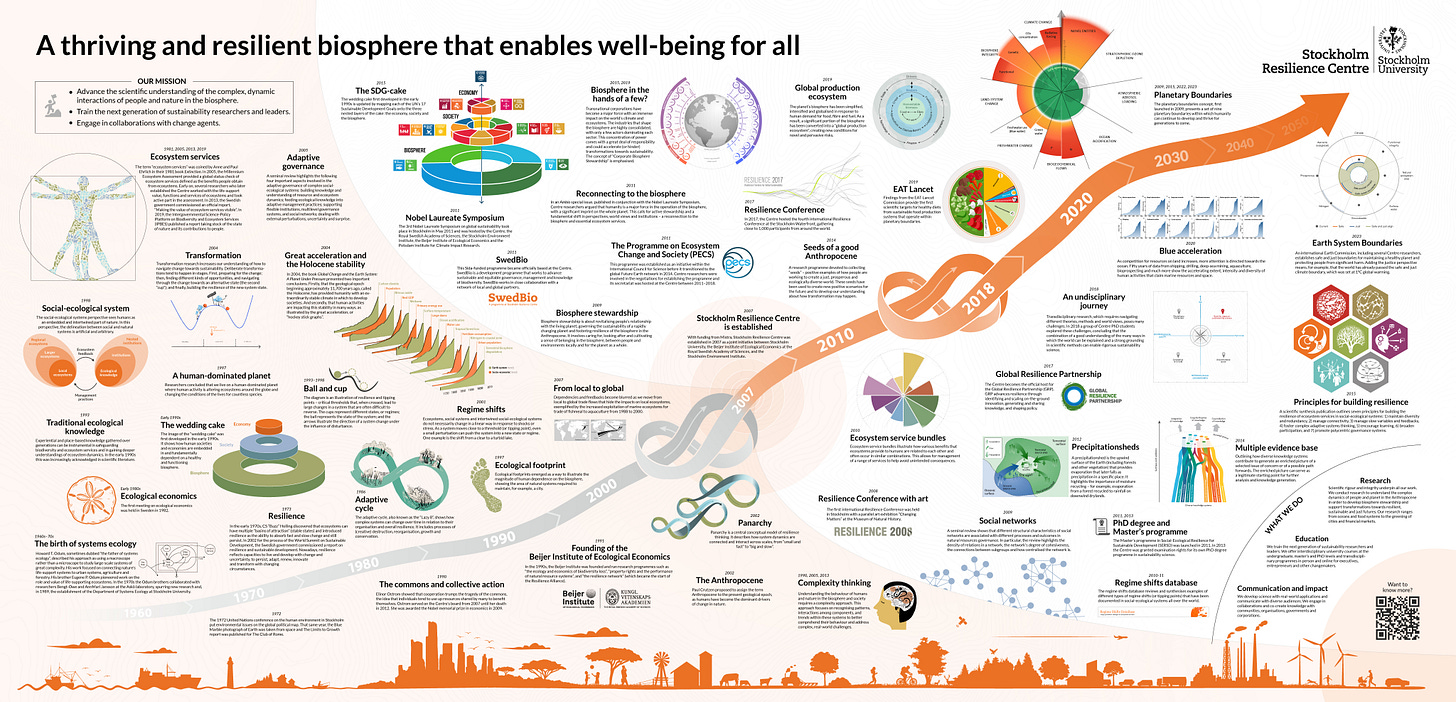

Regen Melbourne and the Stockholm Resilience Centre highlighted looking beneath the surface at trends, mental models, and structures and to use tools like the Iceberg Model, Three Horizons framework, Doughnut Economics, and the Planetary Boundaries. They both implement a significant portfolio of projects, examining resilience and futures.

“A systems portfolio is less about perfect prediction and more about smart experiments in the direction of the future we choose.”

Levers for change

Change comes from many levers working together. We need to engage people, enable leadership, create space for action, and weave in storytelling, art, and connection. Education, finance, and a long-term vision provide the foundations, while acting locally should also connect us to global systems.

Leadership and participation felt different in Scandinavia. Sitting with Goran Carstedt, former President of both Volvo and IKEA, he reminded us that leaders are midwives, helping “birth ideas and giving others the space to act”.

At We Do Democracy and Demokrati Garage, we practiced “Democracy Fitness” with Linea Sveistrup and Johan Galster. This is where disagreement isn’t failure, it’s training. I kept thinking: this is exactly what Tasmania needs when we face choices like industry or development “versus” habitat or tranquillity. Did someone mention a stadium?

Education and storytelling also came alive. In Stockholm, Robert Kautsky welcomed us into Azote’s home-like office, where he showed how art and creative communications help connect science and biodiversity to people. And walking through the Nordiska Museet with Sami leader Inger Axiö Albinsson reminded me that education is about nurturing whole humans, people who can carry complexity and act with agency, not just job skills.

Finance and long-term vision came into focus in Oslo. Over conversations with Knut Kjær, Thomas Berman, Sofie Furu and others, we heard how Norway’s citizens’ assembly on sovereign wealth wrestled with the question: how should sovereign wealth serve future generations? Stewardship costs more upfront but pays off over decades. Imagine a Tasmanian equivalent - a nature stewardship fund that pays landowners over 20 to 30 years to maintain habitat corridors!

And then there was the global context. Meeting three ambassadors in their homes and offices was a reminder that Tasmania’s choices sit inside international systems - from fisheries and carbon markets to geopolitics. Local stewardship only scales when it connects outward. They drove home the need to connect local action with the global context. A huge thank you to Dave Vosen (Australia’s Ambassador to Denmark, Norway and Iceland), Frances Sagala (Ambassador of Australia to Sweden, Finland and Latvia) and Klas Molin (Ambassador of Sweden to Australia) for their generous time and advice. By embedding stewardship in diplomacy and commerce, we can amplify local actions into global influence.

Mix all these ingredients together (leadership, participation, education, storytelling, finance and global connection), and we can bake a system for change.

I left Scandinavia thinking that Tasmania’s small scale and accessible networks could actually be an enormous advantage. If we align these levers, we can show how a community at the edge of the world can lead on stewardship.

Story 3: Food, Waste & Circularity

The power of food to connect

“Where are you planting your potatoes next year? The answer will change you.”

That question landed like a pebble dropped into a still pond. On the surface it seems small, domestic. Underneath it is seismic: what we plant, where we plant, and who plants with us shapes the soil, the economy, the culture and the future. Food is something we all have in common. Over shared meals, listening to chefs who spoke of rescue food and compost, and in conversations that linked farmers with youth, food emerged on the trip as the most practical, human and powerful entry point to systems change.

In Copenhagen and Stockholm food is a civic medium. Chef Matt Orlando reminded us that food connects everyone, but society is losing a connection with how food is grown and prepared. Pella Thiel urged to start small, plant something, re-learn growing, and bring people together across generations. These practices will rebuild relationships with place and with each other.

Food helps us to navigate communication barriers - it’s a natural platform for gratitude, education, and behavioural change. It’s politics, culture and ecology all at once.

Healthy food systems mean keeping production within ecological limits (healthy soils, thriving waterways, biodiversity intact), and ensuring access to nutritious, affordable food and fair livelihoods for producers.

Circularity and designing for regeneration

When you think about waste-to-energy plants, clothes, or real estate finance, you probably don’t immediately think about joy, creativity, or community. Yet in Scandinavia, circularity was everywhere, not as an abstract sustainability buzzword, but as a way of designing for regeneration.

Take CopenHill in Copenhagen. On paper, it’s a waste-to-energy facility. In reality, it’s also a ski slope, a hiking trail, and a public park. The city turned a technical necessity into a social asset. It’s an invitation for citizens to literally walk over their waste and enjoy the view.

Or Houdini Sportswear in Stockholm, where Eva Karlsson and her team treat nature as a blueprint. Their garments are mono-material, biodegradable, and designed to return to the soil. They are closing the loop from clothes → compost → food. Houdini’s message is simple but radical: we don’t need more clothes, we need clothes to do more.

And then there’s Home.Earth, where Rasmus Nørgaard and colleagues are redefining real estate and housing. Instead of short-term returns, they think in 30+ year cycles, designing buildings from upcycled materials, embedding community spaces, and financing projects in ways that align with planetary limits.

“Circular systems ask not ‘how do we dispose?’ but ‘how do we design to return?’”

That’s the shift. Waste becomes feedstock. Outputs become inputs. Value is measured across lifecycles, not quarterly reports.

Scandinavia showed us that small loops add up. City-wide composting. Kitchens upcycling peels into vinegars, oils, and mustards. Farmers rotating crops to heal soils. None of these practices are flashy, but together they knit resilient, circular systems.

We could absolutely do the same here in Tasmania. It’s not a stretch to have community compost and bioenergy hubs, returning nutrients to farms and gardens. Or maybe demonstration farms showing regenerative techniques and hosting farmer-youth apprenticeships? And circular procurement policies for state government, councils, hospitals and schools that prioritise regenerative producers.

“Small loops create big resilience: one community compost hub can seed dozens of regenerative practices.”

If there’s one place we need courage, it’s in our time horizons. Reactive, short-term policy is failing both balance sheets and nature. Scandinavia reminded us that resilience requires patience. We need long-term policy tools like stewardship payments for farmers who build soil and biodiversity over decades, blended finance for circular infrastructure, and regenerative projects that reap social, ecological, and financial returns. Natural resource management deserves long-term investment because it delivers long-term returns for resilience, livelihoods, and cultural pride.

So what does this approach ask of us? To be playful, creative, and practical. Ski slopes on energy plants. Compostable jackets. Community compost bins. Education that doubles as art. Design systems that return, regenerate, and reconnect. Start small. Plant something, compost something, share something. Trust that ripples grow. Regeneration, once set in motion, has its own momentum.

Acknowledgements

A huge thank you to our incredible guides, Kaj Löfgren and Pella Thiel, and to all the generous people who welcomed us, shared their knowledge, and opened windows into new ways of seeing.

Gratitude also to Small Giants Academy and our trip manager Anna Yelland for curating such a thoughtful and transformative journey.

And my fellow travellers Kat Panjari, Ella Andersen, Annabel Phillips, Jen Djula, Jeremy Waanders, Portia Odell, Brenda Nielsen, Annie Nielsen, Mia Ifergan, and Jenny Hall, thank you for the connection, curiosity, and companionship that made this experience so rich.

Finally, thank you to the NRM South Board and team for supporting me to step away from the office to take part in this life-enriching and affirming experience.

I am the CEO of an organisation that works to keep the natural and productive landscapes of Tasmania healthy over the long term. We build partnerships, connect knowledge to action, and help others engage in natural resource management. But the reflections I share here are my own musings shaped by islands and place - they do not represent the views of any organisation. Photos are my own unless attributed.

This story was originally published on Nepelle's wonderful substack: https://nepelle.substack.com/